This is part of a two-essay exploration of urban planning in Munich, Germany. You can read the other essay here.

I turned onto Tumblingerstrasse and the skyline opened up. There was a football-stadium sized clearing in the middle of the neighborhood. All that stood before me were a few small buildings, a handful of tower cranes, and a heap of shipping containers covered with graffiti.

Had street artists bombed a construction site, or had a construction crew bombed an art installation?

When I got closer, I realized that the shipping containers were arranged to form a walkway leading to a three-container high gateway. I walked through and entered a graveyard of out-of service shipping containers, subway cars, boats, trucks, concrete platforms, spiral staircases, and other items seemingly salvaged for their transportation functionality or design qualities. Everything was painted over with tags and murals.

It didn’t take long to realize that no one else was here — wherever here was — and walking through the space felt like being alone in either some kind of a private art playground, or a music venue not yet open to the public.

What was this place?

Nine hours earlier…

I woke up before dawn on the couch of an old college friend. We hadn’t spoken in years, and his hospitality had been very welcome. I tried to return it by showering and packing quickly and quietly. My friend guided me to his local U-Bahn station, and we rode the metro together until I got off in downtown Munich while he continued on to his office.

It was almost 7:30 am. The late November sky was still dark and the streets surrounding the Marienplatz were mostly deserted. I had eleven hours to see the city before heading to the airport for my flight out of Germany.

Rather than reading about the city’s sights and then dutifully going to look at them, I had done some research and crafted a plan that I hoped would give me a more grounded experience of the city.

I’d start at the city’s three remaining medieval gates, or Tors, check out the Eisbachwelle river surfing scene, and then try to track down some of the graffiti murals that had repeatedly come up in my internet search results. This “Tors Tour” felt like a good way to get a street-level look at Munich’s past, present, and maybe even its future.

The Tors Tour

The Marienplatz was the central plaza of “Old Munich” and it remains a central point for the modern city’s downtown. This much was evident as soon as I exited its U-Bahn station (system map, day-pass info). One side of the plaza is dominated by the late-nineteenth century neo-gothic Neues Rathaus, while the other is framed by modern mid-rises. As I walked east from the station toward the Isator, the shops and eateries grew less and less picturesque until I walked past a neon KFC sign. While passing the chicken franchise I noticed the first hints of dawn appear through a gap in the city’s skyline.

That gap was all that remained of the Istator. Rather than being the eastern passage between Old Munich and new, the Isator was no more than three smallish towers and a few arches. But what was no longer present was still apparent.

The buildings outside the gate arced along a curving road that had to be following the footprint of the medieval walls. Those walls were gone, but if I was right, then 681 years after the Isator was built in 1337 its surrounding walls were still very much influencing the look and feel of the city.

The sun fully rose as I walked to Sendlinger Tor, the southern gate. Power cables snaking through the gate led to the stalls and lighting rigs of a Christmastown market, indicating that this Tor was more of a dusk than dawn destination these days.

More buildings continued to arc along the footprint of the former walls beyond the freestanding Sendlinger Tor. A series of scrims featured snow-bound images of Munich’s earlier and fully-walled days, well before it became a bustling international tech hub.

Karlstor, the western gate, is the smallest of the remaining Tors. Reduced to three arches between two buildings, it has been fully subsumed by the city around it.

It only took 90 minutes to see all three Tors, which makes sense since they were built when Munich’s population was about 11,000 people. Today, the largest of the city’s football stadiums holds 75,000.

Still curious about how the medieval walls had impacted modern Munich’s street layout, I grabbed a cup of coffee and waited for the Alter Peter church tower to open its panoramic views to the public at 10:00 am.

At 9:59 an attendant entered the Alter Peter’s ticket booth. One minute later he began letting the small queue of people into the tower. I appreciated the precision exhibited by all involved.

The view from 299 steps above Munich confirmed what I had seen on the ground — the streets within and around Old Munich curved to the boundaries of the Medieval walls. Church towers outnumbered high-rises in the foreground, but in the distance beyond the footprint of the walls, skyscrapers, industrial plants, and construction cranes dotted the landscape as far as the eye could see.

Back on the ground, old and new continued to mix. Delivery vehicles zipped around the stalls of the Marienplatz Christmastown, and like literal clockwork, at the stroke of 11:00 all the automatons began to gyrate and point their smartphones at the rotating figures of the Neues Rathaus’s then 110-years old Glockenspiel.

Scenes From Around Munich

After a short walk north of Old Munich to check out the Eisbachwelle river surfing scene — read all about that here! — I hopped back on the U-Bahn and headed east to see more of the city.

By the time I reached the former royal hunting ground now known as Hirschgarten Park (where I managed to miss both its biergarten and skate park), I had seen enough of the city to recognize that Munich had a healthy amount of street art upon its walls, sign posts, and other surfaces.

The city was by no means overwhelmed, but there were small murals, tags, quick sprays, logos, memes, and flyers throughout Munich, just as you would expect in any other large, dense, Western city. From the Isar riverwalk to the residential Hirschgarten Park, plenty of people had left their mark on the surface of the city.

The more street art I saw, the more I appreciated the counterbalance it provided to the grand monuments of Old Munich. If viewing the Tors, churches, and Glockenspiel was like reading a history book to understand the artistic practices, technology, and mores of Munich’s past, then seeing the street art was like reading an alt-weekly to understand modern Munich. Visually and stylistically diverse, sometimes infinitely repeatable, sometimes bespoke, and much of it easily shared on social media, each piece was a window into the artist’s worldview. When considered en masse, the street art was also a reminder that no matter how much planning goes into an area, people will always find their own use for urban space.

With these thoughts swirling in my mind, I returned to the U-Bahn and headed south of Old Munich to Goetheplatz station to look for that grand cluster of murals on Tumblingerstrasse that the internet had mentioned.

Enter the Viehhof, or How I Accidentally Walked Into the World of Munich Urban Planning

The field of graffiti-covered shipping containers was the Viehhof – a former slaughterhouse and hub of railroad lines for bringing livestock in and fresh meat out of the complex.

After the slaughterhouse shut down in 2007, the City of Munich took over ownership of the land and gave Munich’s graffiti artists, or sprayers, legal permission to write there. Like the Eisbachwelle surfers, the sprayers were allowed to use this space as their own, but unlike the surfers, they used that permission to create a physical “Hall of Fame” to showcase their community’s best work. Giulia Gangl has a good photo of this era of the Viehhof here.

That lasted until 2017, when the City of Munich leased a portion of the Viehhof to Daniel Hahn for five years to be a new home for his mobile music/art/creative space Bahnwärter Thiel. Hahn is one of the leaders of Wannda, eV, a group founded in 2012 that “transforms unused places into a vibrant space for a short time.” Waanda does this with a mix of private financing supplemented with small-scale civic grants, such as this one to fund a public garden.

Hahn knew the Viehhof wasn’t “unused” when he signed his Viehhof lease, and he opened up Bahnwärter Thiel’s shipping containers for the sprayers to write on. However, as one sprayer noted to Kevin Ebert in 2017, “The containers are much more difficult to paint, which is a problem especially for beginners.”

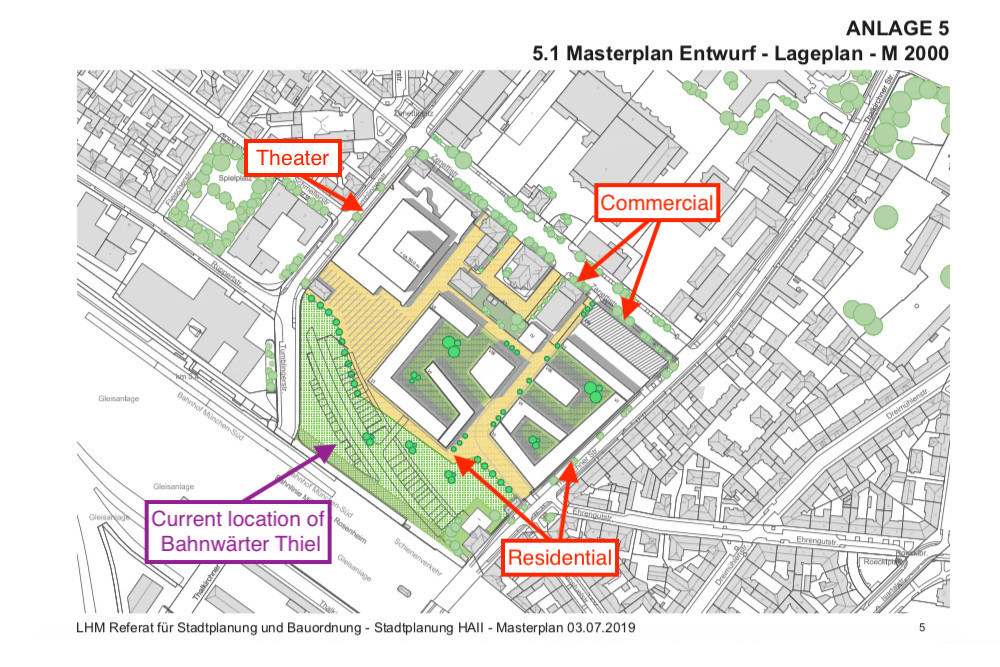

Once Hahn’s lease is over in 2022, a mixed-use development with 600-housing units will be built on the grounds of the former slaughterhouse.

More of the City of Munich’s master plan for the Viehhof is available here.

I didn’t know anything about this shifting land use while I was on the Viehhof grounds, but I still picked up a sense of it. I could tell this was a transitory space. The tower cranes and very moveable shipping containers said as much, and the “NO PHOTOGRAPHY” sign — which I saw much too late for it to be effective* — doubled down on the feeling that conflicting forces of art and commerce were present here.

That NO PHOTO sign may not have stopped me, but it did compound the “don’t linger” alert that walking around a large empty space had set off within my head.

But I did linger, just a bit.

The art was too good here, and it recalled too strong a memory.

New York had a similar space once: 5 Pointz in Queens. A large former warehouse in Long Island City, 5 Pointz was a Mecca for street art… until 2013 when all the art was erased in the middle of the night without warning. Much of its art went unrecorded because developers were too eager to build on the site, a mere two subway stops from Midtown Manhattan. Twin high-rises now tower in its place.

At least Bahnwärter Thiel’s sprayers knew the deadline to record their work. Hahn’s lease with the city has a fixed end date, and the city has a public master plan for the Viehhof’s further development and use. That plan enabled Hahn to sign his lease and create a grand, temporary walled garden of art and culture, but he had done so on top of what had been the sprayer’s space for art and culture.

So Whose Viehhof was it Anyway?

The sprayers were there first, Hahn was there now, and residents would be coming soon.

A common theme emerged as I tried to learn more about the dynamics behind the planning of the Viehhof: Munich is a city with a shortage of both housing and creative spaces. In Der Spiegel, Anke Dürr made the point that “Munich is the city with the highest rent and real estate prices in Germany, [and] every free space is contested.” Laura Kaufmann, writing in Süddeutsche Zeitung, put the housing shortage even more bluntly: “urgently needed apartments are to be built there.”

And yet, despite that urgent need, Kaufmann recognized what the loss of the Viehoff meant to the sprayers:

The cattle farm was one of the last refuges for a freely developing subculture scene. The shrinking of this refuge exemplifies the consequences of the city’s steady growth for free creatives… “There have to be these places where you can just hang out in the city, which remain free of commercialization,” says a young woman. “These places just aren’t there anymore.”

My day in Munich had started as a fun tourist romp, but when I walked through Bahnwärter Thiel’s shipping container gateway I stumbled upon a new kind of wall around the city. Instead of providing protection for those inside of it, this new wall of high rents and dwindling spaces limits what the city can hold, and what can physically be done within its confines.

It also raises some serious questions:

Was an art space for a broader audience more important than free space for people to use as they saw fit?

Was it justifiable to allow an art space to exist if it delayed 600 homes by five years?

What kind of future did Munich hold if it was out of space for any affordable use?

Beyond Bahnwärter Tor

These questions didn’t stop at the doors of Bahnwärter Thiel’s gate. Back on Tumblingerstrasse, I walked further southeast along another curving road, this one alongside the exterior wall of the Viehhof. Sprayers had completely covered both sides of the street with murals, including at least one that was critical of Hahn’s efforts.

Per MUCBOOK, the full black and yellow graffiti originally read, “They say art and mine money. They say free spaces and my securities. Attack railway attendants!”

Bahnwärter Thiel translates to “Railroad Attendant Thiel” in English.

Further down the street, and beyond one elevated railroad crossing, I saw a passenger ship atop another crossing. This wasn’t the remnant of a powerful storm, but the Alte Utting, a 400-person bar that had been installed there by Hahn thanks to yet another short-term lease.

Say what you will about his businesses, but the man wasn’t afraid to dream big.

He also seems to be one of the lucky ones who can afford to dream big.

As I continued walking away from the Viehhof, and after crossing to the other side of its rail yard, the street art murals gave way to a simpler, quicker, and less photogenic form of graffiti which I had seen in other areas of Munich. Much of this graffiti had railed against economic exploitation, police abuse, sexism, racism, and fascism, but one piece beyond the Viehhof stood out from the rest.

“Sell Your Dreams” was a directive, a word of advice, and an option of last resort. It was also a reminder that in a global center of commerce full of sights for tourists and playgrounds for those who can afford to use them, there are plenty of people struggling to get by. And that there are likely more groups beyond the Viehhof sprayers who are being marginalized as this city, like so many other cities, grows upward, but not outward.

One half-day is not nearly enough time to understand a city, but it was long enough to underscore just how much you learn by walking its streets with a critical eye.

When viewed on a map, the layout of a city’s streets may appear largely static as they radiate outward from the city’s core like the rings of a tree. But when you walk the streets, especially those that stand in centuries-old footprints, you see how what surrounds them has evolved time and again with the needs of the city’s people. Just as the width of a tree’s rings signal times of growth or adversity, so do the raising and razing of walls, the digging and re-engineering of rivers, and the laying and overlaying of railway lines. And just like initials carved in a tree’s bark, the surfaces of a city tell the story of those who live on its streets, even as new growth extends further and further toward the sky.

Essay and photos by Dan Meade

Published: 11/15/2020

Date of tour: 11/29/2018

Where do you want to go next?

- What’s modern-day Hiroshima like?

- What the hell is in Western Newfoundland?

- Gilets Jaunes in Nice: What can protests reveal about a city?

* The photos posted in this piece are all from outside Bahnwärter Thiel’s main gate. They do not reveal anything that a pedestrian walking past wouldn’t see. (Return to the essay.)