Of all of the neon-lit, Blade Runner-esque nightlife districts, none felt more frenzied, more concentrated or more disorientating. The city that we were in, the ground that we walked on, must have fueled those sensations – when so many people have died in one place, at one time, the air can carry an extra charge. What had once been a nuclear wasteland was now simply downtown Hiroshima, and everywhere you looked were the signs of a living city that wasn’t haunted by its past.![]()

We arrived in Hiroshima late on a Thursday night in July, and while we didn’t expect anyone to be wearing horsehair shirts or scarlet “A”s upon their breasts, I expected the city to have more of a solemn, serious air to it. Instead, when we left the hotel in search of dinner we ended up surrounded by bars, karaoke joints, restaurants and groups of people moving in and out of all of them. It was just another Thursday night in Japan, full of people letting off steam and having some fun.

We arrived in Hiroshima late on a Thursday night in July, and while we didn’t expect anyone to be wearing horsehair shirts or scarlet “A”s upon their breasts, I expected the city to have more of a solemn, serious air to it. Instead, when we left the hotel in search of dinner we ended up surrounded by bars, karaoke joints, restaurants and groups of people moving in and out of all of them. It was just another Thursday night in Japan, full of people letting off steam and having some fun.

We ended up at Jin-daiko, a Japanese robatayaki (barbecue restaurant) I had found on our hotel map. It was nearly midnight and the place was mostly empty, but that didn’t stop us from drinking a few Asahis and ordering a few plates of meat. The wait staff largely left us alone as we placed the “premium beef” atop the portable charcoal grill and watched the flames engulf our dinner.

The fire danced, moving up, over, and around the meat, as if it were seducing it in preparation to engulf it whole. It was almost hypnotizing to watch how the fire grew and turned brighter as the fat burned and the juices fell onto the coals below. Soon enough, the flames died down, the grill was taken back into the kitchen, the bill was paid and we walked back outside.

By this point, the night was over and the streets were nearly deserted. We made our way back to the hotel but the emptiness of the streets didn’t cause any kind of “spookiness” or haunted feelings. We had seen that Hiroshima was alive and well and not dominated by the ghosts of its past.

The next morning, as we walked to the Peace Park against the current of Salarymen on their way to their desks and cubes, little things began to add up. Compared to the other Japanese cities we had been in, the avenues seemed wider, the streets more airy and the building allowed more sunlight through. The mass transit system felt progressive in its use of busses and trolleys. Trees dotted the streets while green spaces and small ponds full of turtles and fish were found on some corners. All of the buildings seemed new. Then the realization: all of this was because the city had been rebuilt nearly from scratch.

The atomic bomb dropped by the Enola Gay went off right above the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, meaning that the blast went out in all directions from the Hall, leaving it largely intact. Now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome, it has come to symbolize the destruction caused by the bomb, and as such, was high on the list of things to see.

We arrived just before a series of bells went off at 8:15 AM, marking the moment that the bomb had been detonated. Shortly thereafter and while still shooting the Dome, I was approached by Hideo Asano, a poet and writer who seemed to have slept on one of the Peace Park benches the night before.

See the full Manic Hiroshima photo gallery on Flickr!

Asano greeted me from behind, speaking in English and asking me about my thoughts on the bombing. The conversation that followed twisted from his theories on why Hiroshima had not been bombed earlier in the war (because any previous bombings of the city would have made the destruction caused by the atomic bomb seem less total, less devastating), his experiences in Afghanistan under Soviet rule (he did not elaborate fully, but he says he’s not allowed back) and America (where he claims to be blacklisted from the publishing industry). He also read his poem Hiroshima which speaks of how the city was “raised from ashes of cruelty… exhibiting that no one can crush the spirit of Hiroshima.”

He blamed America wholeheartedly for the bombing and spoke as if he could not even conceive of it having been a military necessity (to prevent the millions of casualties that would result from an invasion of Japan), as it is often framed here in America. He went on to place the bomb in a timeline of suffering caused by America’s military that included the use of Agent Orange in Vietnam and led up to the maimed children suffering in present day Iraq. In essence, his message is that America was wrong and evil for dropping an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, and that the act itself was a crime against humanity.

In spirit, his anti-American point of view was more or less what I expected to find in Hiroshima, but Asano was the only one to talk so pointedly on the subject. In fact, perhaps due to the solemn nature of the Peace Park, Asano would be the only person to talk to us there.

Looking beyond the sparse crowds at that early hour, past the Dome and the other memorials, there was the modern city of Hiroshima. The skyscrapers, the baseball stadium and radio towers all loomed over the Peace Park. As young women rode in front of the Atomic Bomb Dome on their bikes and workers strode alongside the river, it almost seemed as if Hiroshima the city had moved away from being the site of “Hiroshima” the event.

This is where the Peace Memorial Museum comes in. It is structured, both in aim and in content, to prevent you from forgetting what “Hiroshima” the event entailed.

Inside, the bombing is presented as much as the end result of Japan’s expansionistic militarism as a horrible act of war undertaken by America. Asano claimed this presentation was the result of an American running the Museum, but the official explanation was that the Museum simply wanted to present what had happened, and why, in hopes that the world could learn from the lessons of Hiroshima. By remaining blame-neutral, the Museum was able to focus on what had happened in Hiroshima and to work towards its goal that no nuclear weapons ever be used again.

Like the city itself, the Museum was not fixated on August 6, 1945, but alive and evolving. The displays, timelines and artifacts that survived the blast weren’t merely meant to strike an educational chord among visitors, but an emotional one as well. Entire rooms were filled with tattered clothing, preserved specimens of warped body parts, pieces of malformed skin and even sections of wall where all that remained of people were “shadows” burnt by the force of the nuclear blast. The Museum avoided being too macabre, but it did not shy away from how the hibakusha (survivors of the bomb) suffered after the detonation.

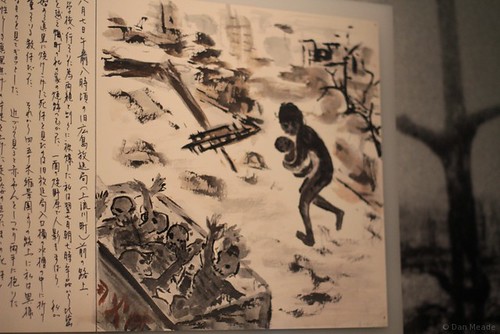

More so than the artifacts, it was the written histories and crude drawings and sketches of the hibakusha that really captured the horror of the attack. Their simple presentation of what life was like in the days and weeks after the bombing was much more vibrant than other displays, like one that featured mannequins of people with melted skin fleeing the burning city.

By the time we left the Museum, a sort of shapeless, indescribable heaviness had begun to sit on my mind and in my stomach. Then I remembered all of the charts and photographs of the world’s current nuclear arsenals that had been on display. For a split second, I began to fear for the future of humanity.

And then I once again looked around and at the skyscrapers, wide streets and legions of people in a vibrant city, one that is alive and growing. Despite all the destruction of the past, Hiroshima was not frozen in the moment that the bomb went off, but was a living testament to the triumph of life over death.

See the full Manic Hiroshima photo gallery on Flickr!

Essay: Dan Meade

Photos: Dan Meade and Rob Bellinger

Publication date: 3/13/2011

Dates of visit: 7/22-23/2010