What’s a Manchester Music Fest?

It sounded too good to be true. Four bands the Spotify algorithm had been serving me — all with outlaw country leanings — were playing the same music festival over Labor Day Weekend 2018. This Manchester Music Fest was allegedly free. You just had to get yourself to Manchester, Kentucky, in the heart of Clay County, in the heart of Appalachia.

That didn’t really faze me. There would be a bunch of people who liked outlaw country, rock, and bluegrass. There would be beer. What could go wrong? Plenty, it turns out, but not enough to ruin a good time.

Before booking plane tickets, I had to make sure the festival was real. I sent its Facebook page a message and received an encouraging response from its founder and president, Tim Parks. As he would later tell us, “We’re just promoting good songwriting, because the mainstream stuff is garbage. We don’t listen to mainstream here.” Those words would come to define our whole experience.

Once we confirmed that the MMF was on, my friend Andrew and I booked flights to Lexington, KY (about $220 each), a car ($18 per day plus fees), and a room at a family-owned motel one town over from the festival ($76 per night). Getting there turned out to be the easy part.

Let me give you a little idea of what it was like to be on the ground in Manchester, Kentucky for this celebration of music and food and culture.

This Story Is Told in 10 Acts:

- Approaching Clay County

- Landing in Downtown Manchester, Pop. 1,255

- An Interview with Tim Parks, The Man With the Plan

- The Friday Night Deluge That Almost Ruined Everything

- Strike One: Meet the Manchester Police

- And Now a Word on the Music (With Audio)

- Strike Two: Chop Meat Leg and the Stuff of Legend

- The Tension Between Clay and Laurel Counties

- MMF’s Impact

- Coda: The Food of the Manchester Music Fest

Approaching Clay County

As a nice older lady at our motel put it to Andrew, “Manchester? You’re taking your life into your hands, going to that town!” She told us that all anyone did there was drink and go four-wheeling. Once in Manchester, we did hear a bit about four-wheelin’, and we did learn the difference between “taxable” and “non-taxable” spirits. But these were not bad things.

We arrived in Clay County on the Friday of Labor Day weekend, just as the latest controversy was unfolding. The local religious folks hadn’t wanted a music festival with beer-wielding out-of-towners circling the square. They fought hard and lost. So when the music festival hoisted a banner proclaiming WELCOME MMF’ERS over the stage, it was like salt in an old wound. It was also the talk of the county.

Here’s a news article covering how the sign was “unintentionally offending guests.” I can assure you that no guests were offended.

If you only go by what you can read online, Clay County sounds like hell. You’ll find articles about obesity, residents voting to take away their own healthcare, vote buying (here and here), the anachronistic worship of coal, and the judicial corruption multiple locals would refer to when we spoke with them. The New York Times ran an editorial about general malaise in the area. And, in a very New York Times move, the paper ranked Clay County the “hardest place in America to live.”

I’m pretty sure that none of the people who wrote those articles were at the Manchester Music Fest. Even so, as we headed east through the hills on the Hal Rogers Parkway that Friday afternoon, we wondered what we were in for.

Landing in Downtown Manchester, Pop. 1,255

On that sunny Friday afternoon, a DJ and MC were getting the small crowd of mostly locals ready. The square in front of the Clay County Administration Building was fenced off to car traffic, with a stage erected in its parking lot. The UPS guy, still working, was making the rounds on foot, dropping off packages at the pawn shop and the police station.

A chainless chain gang of prisoners, all white, moved about the square following their leader, picking up the occasional piece of litter. School was already in session, so curious kids showed up as their classes let out for the long weekend. The crowd stayed pretty thin for a while, and everyone wondered what would happen next.

We grabbed some beers from the West Sixth Brewing trailer. Some of the guys on the chain gang eyed our drinks covetously. We intended to explore the downtown and its gorgeous sandstone buildings, but we ended up standing in the shade and doing nothing, which is normally hard for me to do.

An Interview with Tim Parks, The Man With the Plan

If you stood directly in the middle of car-free downtown Manchester as the festival got underway, you would have no trouble identifying the guy in charge. Tim Parks was the tall, bearded, 30-something gentleman in a tie-dyed t-shirt, running about from vendor to sound guy to vendor to the people managing the VIP meet & greet, with at least one phone in his hand at all times. He spared some time for an interview, and we learned how the MMF got its start.

Tim isn’t a musician — he works for the highway department, also known as the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet. The MMF got started when Tim pitched the idea for a music festival to the county’s new tourism commission. The idea took off, and Tim literally did the booking while he was watching concrete set.

The scene starts with Tim and Kenny Boulin, his friend from local band and MMF performer Bourbon Branch, at a show. I’ll let Tim tell it in his own words:

“We went to a Chris Knight show in Somerset, a couple counties over. Man, it was great. It was a free show. We were drunk, and we had a ride. Kenny says, ‘Man, I wish we could have some cool shit like this.’

‘Cause we’ve got a bad reputation. We’ve had dirty politics. At one time, we had fifteen people, all politicians that’s been elected, been in prison, from all these scandals and all this stupid shit that they’ve done.

So, my boss at work said, ‘Man, you guys keep talkin’ about this… They just put me on this new tourism commission. We’ve had three meetings. Nobody’s turning applications in, nobody’s won any money. You keep talking about, ‘We could do a music fest, it would be popular.’’

He said, ‘Go pitch it’.

So there’s some older people on that [committee]. When guys our age typically go talk to somebody who’s 75, they don’t listen… because they already know more than we do. But, there’s a couple younger guys, plus my boss was on there. I just started talking the game. ‘We can do this’. So they give me two weeks to book this.”

Tim told us what it was like reaching out to the bands’ booking contacts over the web, trying to negotiate fees that would work within the festival budget, and reading through contracts in his work truck at night. Meanwhile, the MMF committee was busy asking local businesses for support and tackling everything from graphic design to stage rental.

Here’s Tim again:

“We ended up, from three people thinking we’re gonna have a cool little party, to having 14 people working their ass off.

We’re just promoting good songwriting, because the mainstream stuff is garbage. We don’t listen to mainstream here.”

The Friday Night Deluge That Almost Ruined Everything

And all that hard work was almost literally washed away in an instant. The weather forecast said it might rain Friday night. The sky looked a little threatening, then terrifying. Gigantic anvil clouds stood up above the mountains and moved on a collision course toward Manchester.

The rain delivered on any threats or promises a thousand times over, cutting short Mountain Heart’s rollicking bluegrass set and threatening to destroy all the sound and stage equipment. I’ve never seen rain like this at any other point in my life. People ran for cover in all directions, some having more fun than others, while the stage crew rushed to lower the canopy over the stage. Then they tarped the big PA speakers, but the wind tore the tarps off almost instantly. The speakers were left to the elements, swirling in the wind and getting drenched by water that seemed to come from every direction.

Flashback to the flash flood that threatened to destroy last year’s @ManchesterMMFER. Thankfully the rain didn’t win. pic.twitter.com/Hl5LI1wVn5

— Rob Bellinger (@rob_bellinger) July 28, 2019

I ended up one of three people sheltering in the sound tent — the tent in the crowd where the Sound Guy mixes audio for the audience. The Sound Guy was hovering over his mixing board, which was set up on a riser, a small stage within the tent. The Sound Guy calmly asked me if I could help hold the tent shut; the clips he brought had been sheared off by the wind. I kept what remained of my beer in my left hand and held one corner of the tent closed with my right. Another festival goer held down the opposite corner.

As water raced downhill, it fanned out across the paved square about an inch deep. This sheet of water rushed through the tent, flowing below the riser, and over my feet. I was standing on the pavement, so eventually my shoes were soaked through.

“I feel bad for them,” said the Sound Guy, talking about the MMF committee. “They worked their ass off for this.” As the rain fell even harder, he got even more dour.

“No way the music will come back tonight. Those speakers are shot. I don’t care, I got good insurance.” He pronounced it in the non-coastal way, IN-surance.

“But I don’t know if they’ll find someone else for tomorrow. Maybe out of Nashville, but not on this short notice.”

I felt really bad for the MMF crew, too. And there were two acts that hadn’t even been able to play yet that night. Once the deluge stopped, silence hung over downtown Manchester. The streets had gone from full-blown carnival to nothingness. It was eerily quiet, cool, and not quite dark.

After some time, guys with leaf blowers took to the stage and started to clear it of standing water. The speakers were tested and hoisted back into position.

The canopy over the stage — holding the WELCOME MMF’ERS sign — was raised, and Julie Roberts would soon go on.

Strike One: Meet the Manchester Police

Here’s a short tale about how my fast food experience may have kept me out of jail.

As we had lumbered about Manchester on Friday afternoon, we noticed that there appeared to be two types of cops on hand for the festival.

The county sheriffs were dressed for war. Helmets, flak jackets, other kinds of bulletproofing. Woodland camouflage in a downtown setting. They didn’t know what they were in for.

The city cops wore t-shirts and baseball caps. They knew exactly what they were getting.

They were getting idiots like us.

After the deluge, there were few humans in the square and an eerie quiet pervaded the cool, mountain air. Where the hell was everyone? The weak had obviously given up and gone home. Others were probably waiting out the weather in their cars, and there was a whole bunch of people huddled in the garage of the Manchester Police Station. One of them was my pal, Andrew.

I waved from the sound tent and walked over. The police station was a single-story brick building, kind of like a big country home, with a flagpole in the front and a radio tower in the rear. On the right side was a single garage bay, which looked like it was used to do garagey things, like basic maintenance on the department’s cars.

Andrew was talking to a small circle of people, all festival-goers. The cops were talking to each other in their own adjacent circle. They all wore the same clothes — minus the ballcaps now that they were indoors — yet it took about half a second to figure out who outranked whom.

I walked up to Andrew’s circle and started to introduce myself. Andrew greeted me by my hitting my right shoulder with this weird slap that knocked my half-empty cup out of my hand. The cup hit the floor of the police garage with a hollow plastic thud. A giant circle of beer foam starting spreading outward from its center.

Everyone was silent. Except for Andrew.

“I apologize for my friend!!” he said.

Then everyone looked at the cops. The foamy circle got bigger. Walking into the police station with a beer and dropping it on the floor was probably how you got put on the chainless chain gang.

“Sorry about that. I’m your guest, and I can clean up after myself,” I began.

One by one, the younger-looking cops looked to the least young-looking cop. All but the most young-looking cop had sharp military haircuts. You could see their brains working to suppress their instincts.

“Just go,” one of them said to me. “ We want you to have a good time here, but—”

“No, I insist, let me take care of this. You must have a mop–”

The cops thought about this for a second. If there were a mop, where would it be? Surely mopping was not in their job description.

Suddenly, what looked like a smirk broke out on the least young-looking cop’s face. He gave me a “hang on a second” look and went through a side door into the main office.

“Am I following you?” I asked.

“You’re gonna stay right there,” said the most young-looking cop. His face remained at a 90° angle to my own and he stood in the stance cops are taught to avoid direct eye contact.

“SIR YES SIR,” I said.

The least young-looking cop reappeared with the mop, which could have been wetter, but whatever. Everyone chuckled. He handed me the mop, and I started into the beer foam. I felt like Pee Wee Herman, washing dishes in the diner after he loses his wallet. But why the hell did I know so much about mopping in the first place?

“You know,” I said, swirling the mop in tight circles, “when I worked at Wendy’s, they made us watch a 30-minute VHS video on mopping.”

“Really?” said the most young-looking cop. “I didn’t know there was that much to know about mopping.” He now made direct eye contact. And we chatted for a little bit about first jobs, and suddenly I wasn’t just an asshole from New York, but an asshole with a mop.

While this was all happening in the garage of the Manchester, Kentucky police station, the sun made its miraculous last gasp, backlighting the stage with soft twilight. The people were coming back in droves for Julie Roberts’s set and the carnival vendors were getting ready to get slammed. The least young-looking cop indicated with a motion of his hand that it was time to get back to patrol, and everyone left the safety of the garage for the uncertainty of the coming night.

And Now a Word on the Music (With Audio)

The MMF committee booked a great bill that leaned towards outlaw country but also included bluegrass and singer-songwriter work. Local bands like Bourbon Branch played throughout the festival, but most sets by national bands happened Friday and Saturday.

Things really got cooking Friday evening with Mountain Heart, a progressive bluegrass band out of Nashville. Here’s a clip of them playing “Blue Night,” the traditional bluegrass number, before torrential rain cut their set short.

South Carolina country singer Julie Roberts and St. Louis blue-collar rockers The Bottle Rockets closed out Friday night. I’ll talk a little more about them later.

Saturday was tons of fun in the off-the-beaten path way that I had hoped for. Texan Ray Wylie Hubbard, a self-proclaimed “acquired taste,” stepped off with his mix of psychedelia, country blues, and beat poetry, all interspersed with droll stand-up. Here he is doing “Mother Blues,” one of his signature tunes.

Only after listening to this recording, 11 months later, did I realize how much this song has influenced a song I’m working on myself.

Next came Kentucky’s native son, Chris Knight. He’s heavily influenced by John Prine but rocks a bit harder with songs that tend to be a bit darker. It was a treat to see him with his full band after seeing him play an acoustic set at Hill Country in Manhattan a few months earlier. Here’s a clip of him starting into “Rural Route,” one of my favorites. The crowd’s a little loud, but I love when the band kicks in.

Whiskey Myers — more Texans — closed out the festival Saturday night, and drew a massive crowd for their harder, Southern rock sound. Of note, Whiskey Myers also drew a much younger crowd. One of the kids behind me told me that his group of friends had come specifically to see that band.

“We need Sturgill Simpson, Tyler Childers. That’s what our generation wants,” he said.

The MMFers had gotten lucky by booking Whiskey Myers just before they appeared in a couple episodes of the TV show Yellowstone. Those appearances had propelled the band’s latest album to the #1 spot of iTunes’ country chart…which caused their booking fee to double.

It was great to see the massive crowd that turned out for Whiskey Myers, and that sight cemented the success of the inaugural MMF. But, like an old man, I wished all those kids had come earlier to hear some of the greats that had influenced the younger band’s sound.

Strike Two: Chop Meat Leg and the Stuff of Legend

Sometimes bad things happen after dark.

Julie Roberts was the first artist to play after the Friday night deluge, and, as Tim Parks put it, “Julie Roberts saved the festival.”

Roberts was the only female performer of the MMF, and just as Tim had predicted, it changed the crowd dynamics, attracting a majority female audience. That audience grew and grew until it became the biggest showing yet. As Tim had also predicted, the ladies brought their boyfriends and girlfriends to see Roberts and her band do their bluesy, two-guitars-and-drums, country rock thing. At one point, she got off the stage and walked barefoot through the wet grass to get closer to her adoring fans.

I liked her set, but I was most curious to see the Bottle Rockets, the Friday night headliner. I’d heard them on Q104.3 in New York when they’d had their one radio hit (“Radar Gun”) in the 90s. Miraculously, they had stayed together and started to lean into outlaw country just as I was discovering the genre. They were older guys, but they seemed to be doing really cool rock stuff that hadn’t exactly been done before.

As the stage crew swapped out the instruments between bands, I noticed that Pat’s Snack Bar, the unofficial headquarters of the festival, had taken on an ethereal glow. As dusk fell, the bar’s neon exterior really popped, reflecting off the wet asphalt. Of course I was gonna take pictures.

As I composed a shot, a voice rang out from the crowd gathered near the bar’s doorway: “Hey you! Why are you taking a picture of that sign? Take a picture of us! Take our picture!”

A nice lady accompanied by two younger women waved and invited me over. They really wanted me to take their picture.

“Let’s use the light from the sign,” I said. They got into position and I took a step back and suddenly one side of my body was falling but not the other.

My left foot made an unnatural motion, like when you roll your ankle walking on an uneven sidewalk, but then my foot went through the pavement. It kept going. My right leg folded up until I smashed my right knee on the pavement. My left leg was…gone.

Where the fuck was it?

It turns out there was some sort of drainage hole in the pavement, with no cover or warning of any kind. It happened to be right in front of the entrance to the bar and was completely invisible at night. You were just supposed to know it was there.

So there I was with my left leg through the pavement, past the knee. My first instinct was to protect my camera. The camera was fine. Now all I had to do was get up. But I couldn’t.

“Well, get the hell up, man,” said some guy. I could only gyrate a bit because my left leg was pinned in the drain hole. I could feel jagged concrete holding the knee joint in place, and the leg was conforming to whatever shape the hole was below the surface. I was one hundred percent sure that my leg was broken. THERE GOES THE FESTIVAL, I thought.

“Oh, shit,” said someone in the crowd, realizing that I couldn’t actually get up. Three guys came over. Two of them got their arms under my left shoulder, the third guy grabbed my right shoulder, and they had to lift and pull, to get me out of the hole. I put my weight back down on my left leg, and it didn’t collapse.

Not broken. FESTIVAL BACK ON.

“Oh, my god,” said one of the women, looking down at my leg, and she looked like she might cry. The crowd of partiers at Pat’s all looked pretty sad.

I looked down at my leg and it was basically ground meat on both sides, covered in mud, with blood starting to seep through.

“That’s gonna hurt like hell tomorrow,” said an older gentleman.

Someone else dragged the owner of Pat’s out to the street, berating him the whole time. “I told you, you better fix that hole, you lazy motherfucker! Look what happened! I hope he sues your ass off!”

A chorus of “sue the city!” broke out as people took cell phone photos of the hole and the leg. Hey, this was just like Queens.

The owner of Pat’s, who was not named Pat, then brought out a useless first aid kit consisting of a first aid kit box that contained only two rolls of bandage tape.

“I’m so sorry, baby. This is my fault that this happened to you,” said one of the women who had asked for her picture to be taken. I tried to convince her that it was not her fault and that I was fine, but that I really needed some paper towels to clean this up. Others approached to offer condolences. Someone offered me a stay on her farm, where we could take a long rest and also go horseback riding and smoke the best chronic in the state, but all I wanted was soap and water.

I finally broke away from the crowd, and as we parted, the well-wishers sincerely offered to pray for my speedy recovery. I washed out the horror wound in Pat’s men’s room, and got back to the stage just as the Bottle Rockets started playing.

They rocked! But the crowd had dwindled to a couple dozen by the end of the set. One of those people was an older guy with a ZZ Top beard and a red, white, and blue cap. He sidled over to Andrew and me at the end of the set.

“You the one that fell?” he asked, in a thick Appalachian drawl. “Fell” is a two-syllable word in the mountains in just the same way that “door” is a two-syllable word in Queens.

I nodded and pointed to the massacre that was my left leg. The stranger took a look.

“Man, my buddy Zeke fell in that hole back in [90-something]! He come out of Pat’s fiddlin’ with his Mӧtley Crüe tape and his Walkman and and fell right in the same damn hole!”

Maybe I would become a part of local lore, too.

“Where you from?” the guy asked.

“New York City.”

“Then you know that the Bottle Rockets were on Q104.3.”

I did know that. But why did he?

Unfortunately my memory cuts out there. And I had to fix up my leg, which sucked because I’d wanted to close out Pat’s with the MMF crew and then try to hitchhike back to our hotel 20 minutes away.

The Manchester Walmart was closed for the night, but the London Walmart, a 20-minute drive away, was 24-hours. I drove us over and got supplies. Back in the motel, I cleaned out the wound and packed it up. I found that it swelled and hurt when I wasn’t standing, so I just stood up the whole next day. My cargo pants came in handy for bandage changes.

The Tension Between Clay and Laurel Counties

Back when we were talking to Tim Parks, he mentioned the surge in local business that the festival had been causing. He pointed out that the tourism board in neighboring Laurel County also noticed that their hotel bookings were up. They ended up kicking in some support for the festival, too.

In Tim’s words, “That’s bridged the gap, because that’s our neighboring county, but for some reason, we never got along.”

By the end of the weekend, we realized that the “city” people from Laurel County were terrified of the “mountain” people from Clay County. Worse, they seemed afraid that Clay County would provide all the evidence to inform our opinions of Kentucky.

And evidence of this tension continued to manifest throughout the weekend. That older lady who said we were taking our lives into our hands? She was from London, Laurel County.

While the folks in Clay County never spoke deridingly of their neighbors, they certainly seemed aware of the way their neighbors spoke of them. I even heard an indirect reference to the inter-county tension from an older gentleman who asked me if I could spare a dollar.

Just before Whiskey Myers played on Saturday night, I needed to swap out the bandages on ol’ chop meat leg. The fresh bandages were in the trunk of the rental car, parked on a dimly lit side street of sandstone buildings. At the end of the street was a narrow swing bridge over Goose Creek that led to the other side of town.

Our rental car had NJ plates and stuck out like a sore thumb. Once I got my new bandages secured and closed the trunk, a bearded man in a button-down shirt approached me and asked if I could spare a dollar. I surprised him by offering two, and he surprised me in return by asking if I would like to take his picture. I thought the swing bridge could make for an epic shot, and he seemed to agree.

As we walked over to the foot of the bridge, he told me he was embarrassed to ask for money, but he needed to do so while “my mother’s money is tied up in Corbin,” something to do with the courts. Corbin is in sits adjacent to Laurel County. (Update: As an astute observer pointed out, Corbin is not actually in Laurel County. It’s in Whitley and Knox Counties. But, according to Wikipedia, “The urbanized area around Corbin extends into Laurel County; this area is not incorporated into the city limits due to a state law prohibiting cities from being in more than two counties.“)

If you were going to panhandle in Manchester, maybe it was more believable — or just true — that your money was tied up where the rest of the money seemed to be.

Just then, Whiskey Myers took the stage and I had to hurry back a few blocks. During the band’s set, one young guy from neighboring London (Laurel County) put me in a drunken bear hug and told me my camera made him nervous, that he was afraid we would make fun of Kentucky in our writings, that we would come to the festival “and write, ‘Now, they’s fuckin’ their sister over in Clay County.’”

This each-isn’t-sure-of-the-other dynamic reminded me of our first College Point Class Conflict Pub Crawls, in which every group was afraid that every other group would make fun of them. But then everybody just had a beer and a good time.

Again, to use Tim Parks’s words, “Hell, we’re all pretty much the same people from the same descendants. You know, Eastern Kentucky is weird. When you’re going through Wisconsin… you don’t know what fuckin’ county you’re in. You know you’re in Wisconsin.”

In Kentucky, your county represents your origin and your identity. But there are a few things that tie the Appalachian region together.

Again, Tim Parks: “Eastern Kentucky is a little bit different because of all these mountains and a real strong accent. And the heritage, the bluegrass music.”

The beauty of the MMF was that it brought people together to celebrate appreciation of a common culture, while injecting dollars into the local economies

After we returned to New York, people there asked us if everyone in Appalachia was white. Well, mostly, but not entirely. They also asked us if Appalachia was Trump country. In three days, we saw one guy in a Trump shirt: a white senior citizen deeply engrossed with his paper tray of nachos.

MMF’s Impact

By the time Whiskey Myers took the stage Saturday night, there was no question about the festival’s success. Tim Parks had pointed out that both beer and barbecue sold out the night of the deluge, but now the square itself was ‘sold out,’ with thousands forming a V-shape where two roads met. People had come from multiple states and there were even a couple tourists from the UK. The local hotel and campground sold out, the vendors and artists made money, and thousands got to experience a slice of American musical culture in a unique place they may not have gotten to see otherwise.

I couldn’t help but remember Tim saying, “We don’t listen to mainstream here.” The MMF was a celebration of culture by and of the people, and we’re happy that it will happen again in 2019.

Fortunately, there was no third strike that weekend.

Coda: The Food of the MMF

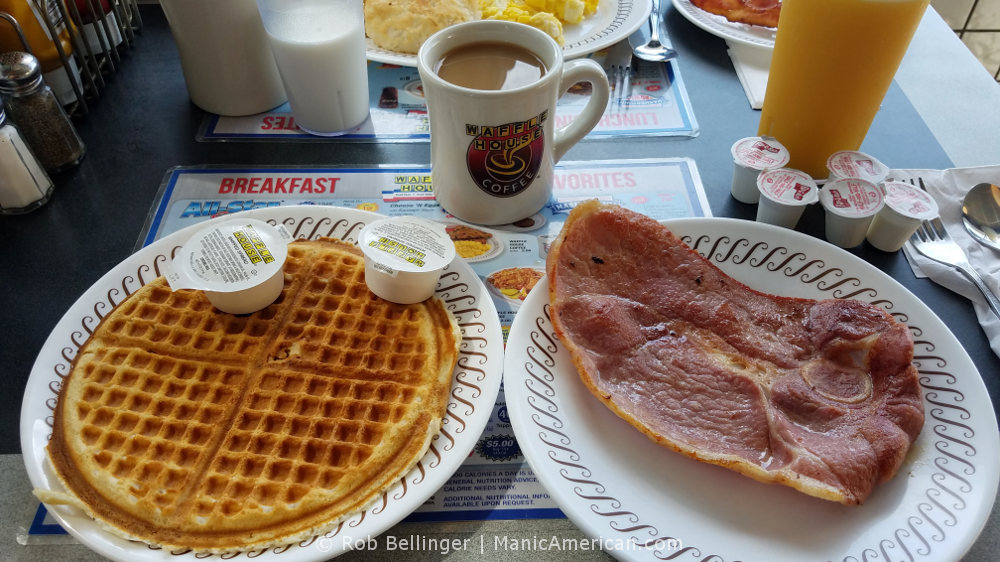

Do you think we would create a post that doesn’t mention food? Here are a few favorite meals from the MMF ‘18 trip: Country ham and a classic waffle at the London Waffle House, a perfect “RB test burger” at Pat’s Snack Bar (American cheese, grilled onions, grilled jalapeños), served on a potato roll, and a great smoked pork sandwich with cider vinegar sauce from the Roll ‘n’ Smoke truck out of Lexington.

Words, photos, and audio by Rob Bellinger

Publication date: 8/11/2019

Date of festival: 8/31 – 9/03/2018